Chapter I

BACKGROUND INFORMATION

1.0 Introduction

This chapter talks about the background information about the geography, the peoples, and languages of the central Ifugao people and their relationship with other languages and nearby peoples groups.

1.1 The name of the language

The language variety spoken in the central Ifugao is known to other Ifugao tribes from the adjacent municipalities as the “munkalyon” which literary means ‘those who say kalyon’ and the “mungkgokikgo” as a way of distinguishing the language variety from the “mun’alyon, the “mun’ibanawol” , the “mun’ikiangan”, and the “mun’iyayangan”.

At present the “mungkgokikgo” , a language variety spoken in baranggays Burnay, Boliwong, and Tungngod (that used to include Lagawe Proper) are now being assimilated to the munkalyon. The two are very similar except some few lexical terms; and one of which is the particle “kgokikgo” whose counterpart in the munkalyon is “boppo’oh”. In this paper, I refer to the munkalyon and the munghokigho as the central Ifugao language.

People groups from the southern (Lamut) and south-western (Kiangan, Asipulo, Tinoc) and North-western (Ayangans) sometimes choose to refer to the people by the general location, instead of the language and called them “ihuddokna” or ‘(people) from the north’; and when they do that they lump the speakers of both the “mun’alyon” and the “munkalyon”; and they sometimes includes speakers of the “mun’ibannawol” that lived farther north of Hingyon municipality.

The people prefer to refer to themselves by their respective place-names: thus both the people groups from the northeastern baranggays of Hingyon that speak the “mun’alyon” dialect, and from the southwestern baranggays of Hingyon that speak the “munkalyon” dialect call themselves either “ihuddoknah” or ‘from the north’ or “ihingyon” or ‘from Hingyon’; and the people from the adjacent baranggays of Lagawe also identify themselves by their place-name refer to themselves as “ilagawe” or ‘from Lagawe’. Both of these groups though speak what I refer to as the ‘central Ifugao language’.

1.2 Ethnology

The dominant economic activity of the people is wet-farming; and even a major part of its religious activities are related its annual farming cycle; and its social leader is one who has had the historically largest land holdings. Supplemental economic activities are combinations of two or more of the following: livestock raising, vegetable production, wood curving, furniture production, micro-business ventures, and various kinds of employments.

The land is largely mountainous and all the higher elevations were covered with communal and family owned forests; the lower hills are dedicated to either housing or to orchard or a combination. Farm lands (wet fields and dry farms) are found along rivers and their tributaries from where irrigations are also drawn. Stone walls are found in rice fields and residential lands. Traditional houses are raised about the ground and were made from a combination of wood, bamboo, and thatched roofing. Modern houses that are made of a combination of reinforced concrete, wood, and galvanized sheets roofing are now replacing the traditional ones.

1.3 Geography and Demography

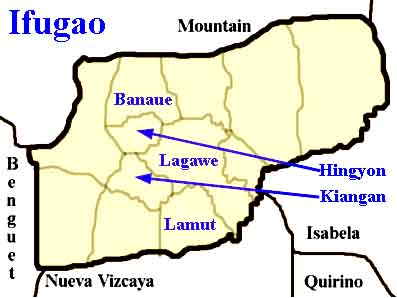

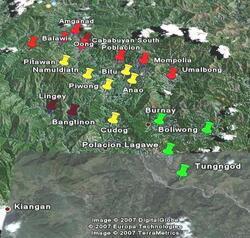

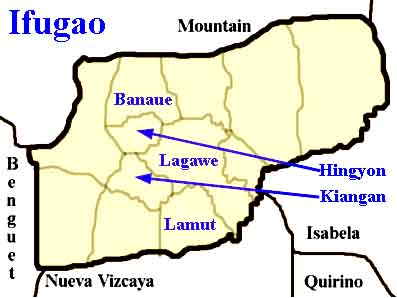

The language is spoken by inhabitants occupying the general location between latitude 16 52’ 41’’N and 16 47’ 02’’ N and longitude 121 03’ 45’’ E and 121 09’ 20’’ E (http://www.flashearth.com/ google earth, accessed Nov 24, 2007). Digital aerial map marked Map #1 (on following page) and drawn map marked Map #2 show the where the central Ifugao language variety or the “munkalyon is located in relation with the northern Ifugao language or the “mun’alyon” variety is located.

1.4 Physical location

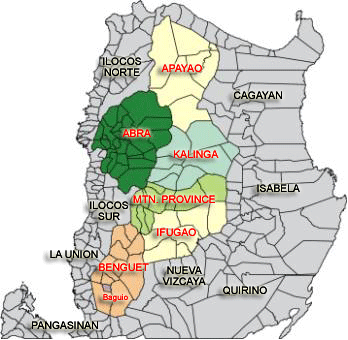

The homeland of the Ifugao (L-complex) language is situated at the central portion of the Cordillera mountain ranges with altitudes ranging from 4,000 to 5,600 feet above sea level. It occupies less than 750 square miles (Bankoti 2004) in center of Northern Luzon.

At the central portion of this land, lies Hingyon-Lagawe, the home of the central Ifugao language variety. Hingyon-Lagawe is generally mountainous and it is bounded on western portion by the Ibulao river, on the southeast by the ridges along Tungngod-Pulaan boundary then to the Boliwong-Jukbong boundary , up to the Burnay-Umalbong boundary; on the northeast by eastern ridge dividing baranggay Anao and Mompolia, and baranggay Bitu and Baranggay Poblacion, and northeast by the political boundaries between Namulditan and Cababuyan, and between Pitawan and Oong; and on the southwest by the mountain ridges along the boundaries dividing Baraggays Namultitan-Piwong-Cudog and Bangtinon and down to the Ibulao river.

Google map of Hingyon-lagawe

The other maps marked Maps #2 and #3 show the general location of land inhabited by the Ifugao tribes in relation to the provinces of northern Luzon, and geographical relationship among the municipalities of Ifugao.

Map #2 above shows the eleven municipalities of the province of Ifugao. The speakers of the central Ifugao language inhabited the southwestern of Hingyon municipality and the western portion of Lagawe Municipality. For lack of an appropriate term, the “munkalyon”

language variety is referred to here as the ‘central Ifugao language’. North of it are speaker of the “mun’alyon”; to the east are the speaker of the “mun’iyangan’; to the south are speakers Ilocano and Ayangan; and to the is largely the speaker of “tuwali” and “kelei”.

The speakers are largely monolithic, or the people speak the same language. Where there are speakers of the other languages they tend to learn and speak the host language. The four baranggays: Poblacions East, West, North and South of Lagawe is different. There are minority speakers of Ilocano, Tuwali, and Ayangan, and even Tagalog.

The language is used in the homes, in social gatherings, in school campuses (except in class rooms), and in churches. Ilocano and central Ifugao language are largely used when transacting business; Ilocano when either one of the seller or buyer is an Ilocano. Some Ilocano entrepreneurs and residents are trying their best to speak the local language. English is used in written communication among offices, both private and public; while Ilocano and vernacular are used in oral communications both private and public establishments.

The interactions among language speakers are very cordial and friendly. People generally have the tendency to speak the host language where ever they are. The “Munkalyon” or central Ifugao language variety and the “tuwali” language are markedly dominant among all other language. Speakers of these two languages tend to speak their respective language where ever they are, even when they are in any of the adjacent provinces; when speakers of the two language groups meet, each language group speak their own respective language when interacting or conversing with the other. It may be because the two language varieties are very similar and understandable among them.

In terms of temperament, both the “mun’alyon” and the central Ifugao language speakers, the “munkayon” equally dominant. This trait is observable in political activities, employment in government offices, in leadership in religious organizations, and in police blotters.

1.5 Genetic affiliation

The central Ifugao language is genetically affiliated with the Northern Philippine languages (McFarland 1980 and Ethnologue 2000). The ethnologue however further subdivided Northern Philippine languages into Northern Luzon and Southern Luzon, whereas McFarland considered it as one gene languages. McFarland divided the Northern Philippines languages into cordillera languages, Ilongots , and Sambalic languages; cordillera languages was in turn divided Dumagat languages, Northern cordillera languages, Ilocano, Central cordillera languages, and Southern Cordillera languages; Central Cordillera languages was further divided into Kalinga, Itneg, Balangaw, Bontoc, Kankanaey, Ifugao (L-complex), and Isinai; finally, the Ifugao (L-complex) languages was subdivided into Ifugao-Eastern, Ifugao-Kiangan, and Ifugao-Banaue. The genetic affiliation of the Ifugao (L-complex) language following McFarland model would then look like Figure 1.1 below. It can be contrasted to that of Gordon found in Etnologue in Figure 1.2 and also that of Reid’s, Figure1.3.

Figure 1.1 McFarland 1980